The role of women in Vancouver society changed dramatically during World War II. As this period was transformative for all Canadians, the nation demanded maximum commitment from its civilian population. Canada needed women to step up and support the war effort—both at home and in jobs traditionally held by men, and even within the military itself. Vancouver women enthusiastically embraced their new responsibilities and actively contributed to the success of Canada’s Victory Campaign. Read more at vancouveryes.

Stepping Up: Women on the Civilian Front

During the war, many women moved into civilian positions previously held by men. Vancouver even saw its own version of “Rosie the Riveter”—the symbolic worker who toiled in factories to support the war effort. Women worked alongside men in plants, air bases, and on farms. They manufactured parts for ships and aircraft, as well as various munitions. Women drove buses, taxis, and streetcars. This level of participation was unprecedented for Canada—countless Vancouver women proved they had the skill, strength, and ability to perform duties they typically never would have considered. Additionally, women expanded their charitable activities during the war, focusing on supporting the military effort. They knitted socks, scarves, and mittens, prepared care packages for Canadians overseas, collected materials for scrap drives, and aided those affected by the war. They provided clothing and created refugee centres. Furthermore, to cope with wartime shortages, women became virtuosos of wartime thrift. They sewed clothes themselves (sometimes even using old parachutes to make a wedding dress) and created “Victory Gardens,” ensuring their families and communities had necessary fruits and vegetables.

Many Vancouver women sought to take an active part in the war and demanded that the government create military organizations for women. Canada’s armed forces were permanently changed between 1941 and 1942 with the creation of female divisions. For the first time in history, women were given the opportunity to serve Canada in uniform, with over 50,000 women enlisting. Most of them served in areas that came under enemy fire.

The Enduring Legacy of Women’s Wartime Service

The collective experience and achievements of Vancouver’s women and men during the immense challenges of the Second World War formed a vast legacy for the country, one that remains an important part of its future.

For instance, Veterans Affairs Canada’s “Canada Remembers” program encourages all Canadians to learn about the sacrifices and achievements of those who served during both war and peace. It also invites Canadians to participate in memorial events that will help keep this part of history alive for years to come.

The Story of Burrard Dry Dock: Before and During the War

Burrard Dry Dock (BDD), located at the foot of Lonsdale in North Vancouver, is a symbol of the city’s shipbuilding history. More specifically, it serves as a powerful reminder of the enormous contribution local women made during the Second World War. Initially called Wallace Shipyards, BDD began its humble operations in 1894. It was a backyard business started single-handedly by Alfred Wallace. His first contract was to build lifeboats for the Canadian Pacific Railway, and he had only one assistant: his wife. In 1906, he moved his operations to the North Shore of Burrard Inlet. Despite a devastating fire in 1911, the business began to grow. In 1921, Wallace Shipyards was renamed the Burrard Dry Dock Company. After Alfred’s death in 1929, the business passed to his son, Clarence.

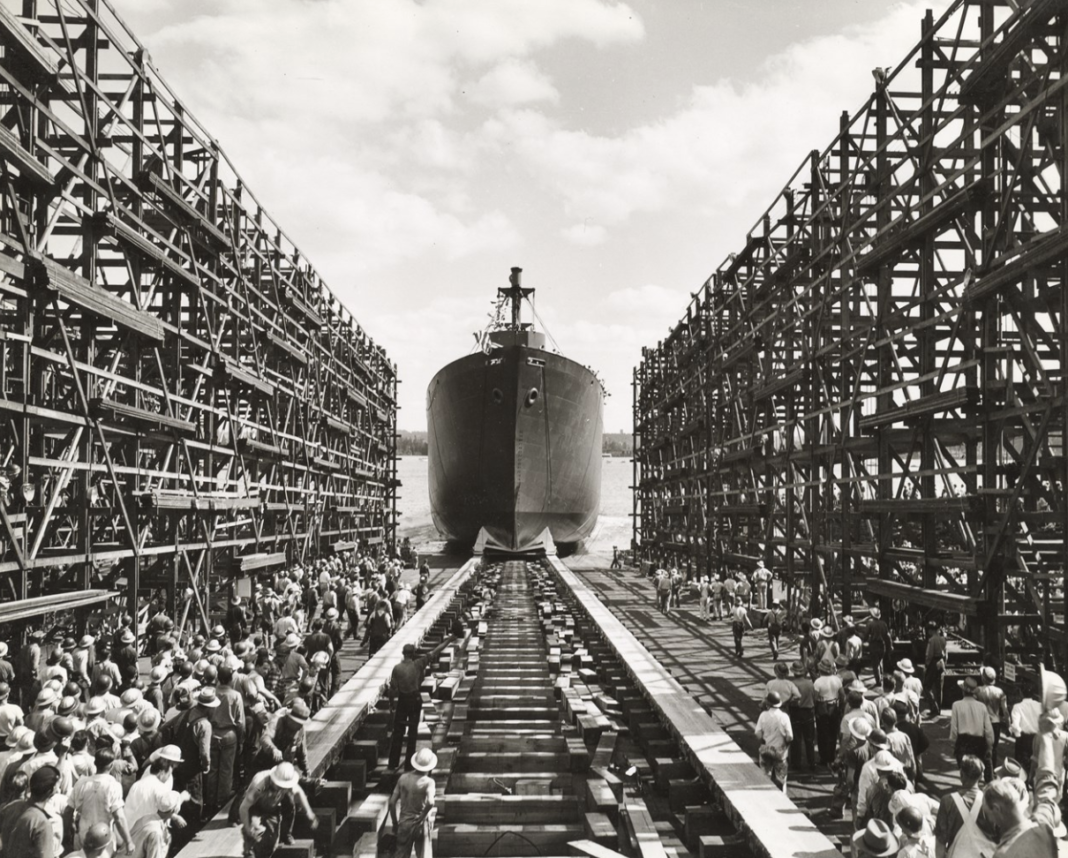

Before the war, the company’s activity was primarily focused on ship repair, with only occasional construction of small ocean-going vessels. One of the most famous ships built at Burrard Dry Dock was the St. Roch in 1928—a Royal Canadian Mounted Police Arctic patrol vessel that is now the central exhibit of the Vancouver Maritime Museum. During the war (1939-1945), Burrard Dry Dock expanded significantly, adding the South Yard to its original North Yard. Together, 109 ships were built during this period. In cooperation with the neighbouring North Van Ship Repairs, they produced approximately one-third of Canada’s WWII naval vessels. The workforce also grew substantially during this period, reaching 14,000 employees.

Welding the Way: Women at the Dockyard

The corporate newspaper *Wallace Shipbuilder* was published monthly for Burrard Dry Dock employees from July 1942 to September 1945. This publication provides valuable insight into the period of rapid wartime growth and production, as well as the opportunities for women workers. The first women arrived at the North and South Shipyards in September 1942. According to an article in the *Wallace Shipbuilder*, the shipyard foremen and male workers were “not very impressed and gave a cold welcome” to these women entering a man’s world. Imagine how unpleasant that must have been! But these women rolled up their sleeves and got to work, quickly earning the respect of their male colleagues through dedication and tenacity.

By the spring of 1944, there were already 1,000 women working at the shipyards, directly involved in building ships. They were not restricted to just office or simple cleaning tasks—they demonstrated their abilities in precision work across electrical, metalworking, and machine shops. They worked alongside men in pipe, sheet metal, and blacksmith shops, performing duties as shipwrights, drill press helpers, welders, burners, and riveters.

Women also worked in the steel shop and template shop, operated lathes, drove trucks, wrapped pipes with insulation, and cleaned hulls.

During the war, women experienced workplace equality for the first time. At Burrard Dry Dock, they received equal pay and access to the same medical and housing benefits as men. However, this employment equality was short-lived. After the war ended, women at Burrard Dry Dock were largely forced to vacate their positions in the shipyards to make room for men returning from military service. When manpower was severely lacking during the war, companies willingly built separate facilities for women (restrooms and change rooms) to accommodate the new workers. Yet, after the war, employers like Clarence Wallace argued that maintaining separate facilities for women would be impossible, costly, and inconvenient. Moreover, women who remained working often faced social criticism from both men and women. They were often insulted for allegedly “taking” jobs from able-bodied men. Post-war society sent them a clear message: “Okay, ladies, thanks for participating, but the war is over—time to get back to the kitchen!” For some, this may have been acceptable, but for many, this experience was the impetus to strive for something more, having realized the full power and might of their being.