In September 1941, people in Vancouver lived somewhere between long workdays and constant worry. Every morning, hundreds of workers streamed into the North Vancouver shipyards, where ships for the Allies were being assembled. Everyone understood one thing: the pace couldn’t slow down. Wages were rising, new workers kept arriving, and housing was disappearing faster than builders could put it up. Long before sunrise, the city was already awake — crowds headed to factories, ports, and night shifts.

Alongside all this rush, another reality unfolded. On Powell Street, Japanese Canadian families waited for government decisions and tried to ignore the growing rumours spreading through the city. Vancouver felt the war inching closer, even though the front was still far away. This mix of routine, fear, and constant mobilization shaped life in the fall of 1941. Read more at vancouveryes.

Shipyards as a Path Out of Hardship

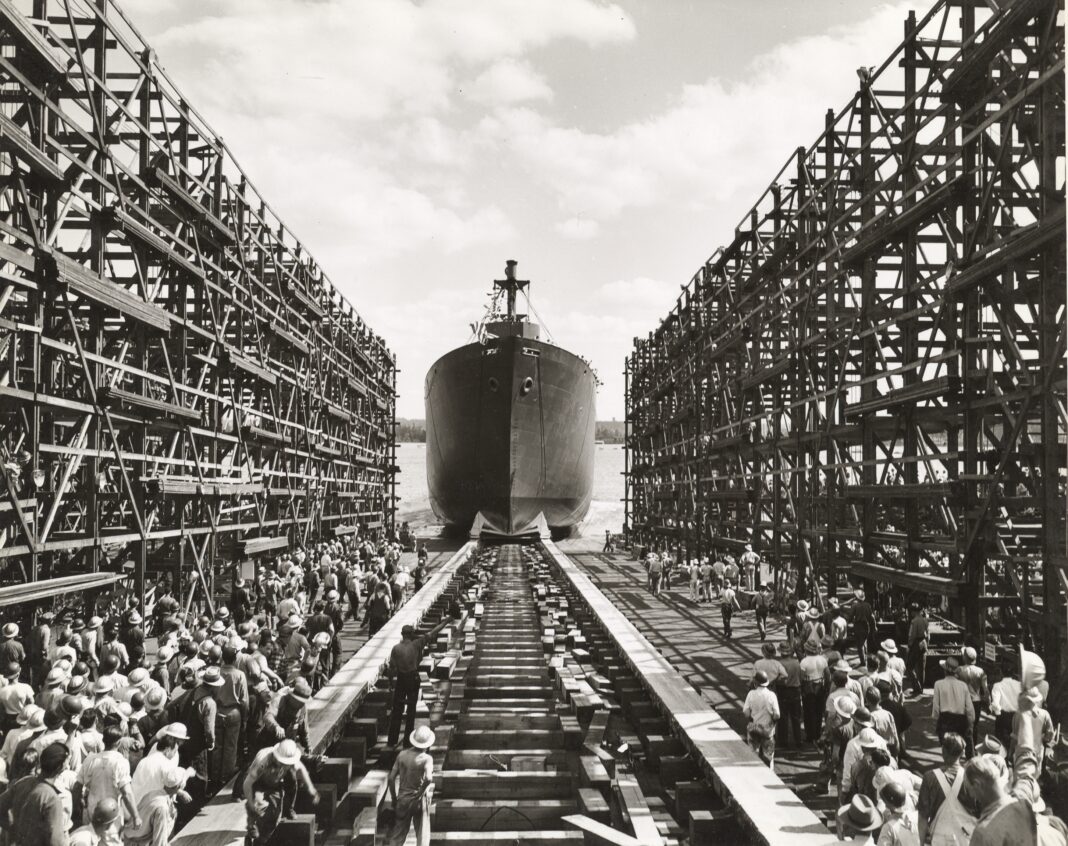

The most dramatic changes that September were felt by shipyard workers. Thousands headed to Burrard Dry Dock in North Vancouver. The shipyards ran around the clock as Canadian builders assembled cargo ships for convoys bound for Britain. Sheets of steel filled the yards, and workers cut them almost without pause. Inside the workshops there was only the heavy thud of hammers and the steady buzz of welding torches. Every ship mattered to the Allies, and people talked about that even in lunch line conversations.

The demand for labour grew so quickly that shipyard managers began hiring women. Many completed short welding or riveting courses and, within weeks, worked alongside men at the same level. Teenagers also found ways to help — delivering messages, carrying parts, and assisting where needed. In the city, people joked that anyone who wanted a job could find one in a day. For many families, wages finally allowed them to buy more food, clothing, and even save a little, though food prices were slowly climbing.

The industrial boom changed Vancouver almost overnight. Workers arrived from other provinces, and neighbourhoods couldn’t expand fast enough. Construction crews put up temporary houses, and families often shared small apartments with relatives. Schools added desks because classrooms filled up faster than anyone expected. Evenings brought crowded buses and streetcars as exhausted workers returned home. Somewhere in the city, something was always being built or repaired, and that constant movement left people drained.

Still, these jobs gave many families their first real chance to avoid poverty during the war. Some paid off old debts; others saved for a new home, even if finding one remained difficult. But everyone understood one thing: as long as the shipyards kept running, they had steady income and at least some confidence in tomorrow.

Urban Infrastructure Under Pressure

By September 1941, housing had become the biggest challenge for anyone arriving to work in the shipyards or the ports. Apartments disappeared within hours of being listed. Families squeezed in with relatives or friends, and sometimes three or four adults shared one room. In Point Grey and Mount Pleasant, small wooden homes often had someone sleeping in the basement on a makeshift bed. Workers said they sometimes moved several times a year because landlords raised the rent or gave the room to someone else.

Construction companies worked almost nonstop. North Vancouver saw entire rows of temporary houses built for Burrard Dry Dock workers. Prefabricated panels arrived on trucks, and crews assembled them in just a few days. The houses were small and poorly insulated, but they gave shelter to people arriving from Alberta, Saskatchewan, or Vancouver Island. Some families received units in new municipal housing projects that expanded just as the city began struggling with the influx of newcomers.

Schools filled just as fast as apartments. Teachers added extra desks, and children often sat on folding chairs along the walls. New students came almost daily, so schools opened temporary classrooms in gymnasiums. Hospitals felt the same pressure — lines grew longer, nurses worked more shifts, and some clinics extended their hours.

Public transit also felt the strain. Buses and streetcars were packed even before the morning rush, since workers headed to their shifts at all hours. People stood shoulder-to-shoulder, and drivers kept asking passengers to move further inside, even though there was hardly any space left. Some routes added more runs, but they only eased the load a little.

Social Shifts and the Role of Women

As more men left for the front, women stepped into industrial jobs across Vancouver. At Burrard Dry Dock, they worked as welders, riveters, and quality inspectors. Teenagers stood beside them as apprentices or helpers. Every day, hundreds of women arrived for their shifts in coveralls and heavy work boots — something few could have imagined only a few years earlier.

Yet after long hours at the shipyard, they still returned home to the usual responsibilities. They cooked, cared for children, and tried to manage everything they once shared with their husbands. Many woke before dawn to get kids ready for school, finish a shift at the yard, and return home late in the evening. Families created new routines: older children took on household tasks, and neighbours helped one another when they could.

Slowly, Vancouver’s view of women’s work began to change. Women who learned industrial skills felt more confident; they understood complex equipment and earned steady wages. A new generation was forming — one for whom paid work would feel normal. After the war, many no longer wanted to return to the way things had been.

Civilian Mobilization

Across the city, people joined any effort that could support the front. Volunteers collected warm clothing, organized scrap-metal and rubber drives, and helped in hospitals. Fairs and gatherings across Vancouver raised money through war bond sales. In many schools, children brought newspapers and tin cans, believing their contribution mattered too.

Meanwhile, workers joined unions to protect their rights during the intense production demands. Many worked overtime, and unions pushed for safer conditions and fair pay. Negotiations were difficult, but workers didn’t want to risk production delays — each completed ship mattered to someone fighting overseas.

There were also regular meetings for families of servicemen. Nurses and counsellors held support sessions, newspapers printed stories about local soldiers, and radio broadcasts helped keep spirits up. Vancouverites tried to hold together and believed the war would eventually be won.

What Worried Vancouverites?

In the early months of the war, many feared an attack from the Pacific. People followed news from Hong Kong and Pearl Harbor, and volunteers patrolled the coastline. Schools held air-raid drills, though most children didn’t grasp how real the danger might be.

Japanese Canadian families faced the most pressure. Many lived in Strathcona or along the waterfront, where fishing had been a family trade for generations. After the war began, they faced suspicion, searches, and the first administrative restrictions. Some men were detained “for examination,” and businesses lost customers. Still, families tried to keep daily life going, even as uncertainty grew.

Tensions appeared in other ways too. Some blamed new workers for rising prices; others argued about shortages and long lines. At the same time, many communities tried to support each other. Neighbourhood committees helped distribute food, and church groups raised money for families who had lost their income.

Sources:

- https://www.cnv.org/Parks-Recreation/The-Shipyards/About-The-Shipyards

- https://monova.ca/north-vancouvers-wartime-shipbuilding-waterfront/

- https://www.coquitlamheritage.ca/our-blog/vancouver-ship-building

- https://www.nsnews.com/in-the-community/time-traveller-second-world-war-forces-north-van-shipbuilding-boom-5920398

- https://scoutmagazine.ca/how-1000-vancouver-women-fought-world-war-ii-from-the-north-shore

- https://britishcolumbiahistory.ca/sections/periods/World_War_II/Burrard_Shipyards.html